When Hydrostatic Head Is Not the Primary Barrier

In conventional drilling, the hydrostatic head of the drilling fluid is widely accepted as the primary barrier against formation influx. If the mud weight is sufficient to keep bottomhole pressure above formation pressure, the well is considered statically overbalanced. The blowout preventer (BOP) stack then serves as the secondary barrier if the primary fails.

However, this understanding does not apply universally to all drilling, completion, and intervention operations. In many operational modes, hydrostatic head either does not qualify as a formal barrier or is only one component of a larger pressure containment system. The difference lies in how bottomhole pressure is maintained and whether that pressure can be independently verified, tested, and relied upon.

This article clearly explains what changes, why they change, and when, using a logical progression from conventional drilling to more complex operations.

Key Questions Addressed

Is hydrostatic head always the primary well control barrier?

When does hydrostatic head cease to be the primary well control barrier?

Why do certain standards exclude fluid weight from barrier definitions?

How do MPD, coiled tubing, and underbalanced operations redefine well control philosophy?

What qualifies as a valid barrier in modern well integrity practice?

How should drilling professionals think about barrier envelopes during dynamic operations?

1. The Foundation: Conventional Overbalanced Drilling

In traditional drilling operations, well control is achieved by maintaining sufficient mud density so that the hydrostatic column provides a bottomhole pressure greater than the formation pressure. This condition ensures that the well is statically overbalanced at all times.

In this case, hydrostatic head qualifies as the primary barrier because it independently prevents influx. It does not rely on active systems or surface-applied pressure to remain effective. If circulation stops and surface pressure is lost, the hydrostatic column still maintains control. The BOP stack remains the secondary barrier, available if the primary barrier fails.

This static, self-sustaining nature is what makes hydrostatic head a valid primary barrier in conventional drilling.

2. Managed Pressure Drilling (MPD): When Hydrostatic Alone Is Not Enough

Managed Pressure Drilling changes this philosophy by intentionally manipulating surface backpressure to precisely control bottomhole pressure. In many MPD applications, especially Constant Bottomhole Pressure (CBHP) mode, the mud weight alone is insufficient to maintain overbalance. Surface backpressure applied through an automated choke system becomes essential.

In these cases, bottomhole pressure is the sum of hydrostatic head, friction pressure, and applied surface backpressure. If the surface choke system fails or pressure is unintentionally released, the bottomhole pressure drops immediately. This means that hydrostatic head alone is not sufficient to prevent influx.

Therefore, in CBHP MPD operations, the primary barrier is not just the mud column. It is a managed-pressure system that includes the rotating control device (RCD), choke manifold, control software, and closed-loop circulation system. The barrier becomes dynamic and dependent on active control.

However, in overbalanced MPD, where mud weight alone is sufficient, and surface pressure is used only for fine-tuning, hydrostatic head can still be considered the primary barrier. The distinction depends entirely on whether the well remains overbalanced if surface pressure is removed.

3. Underbalanced Drilling (UBD): Intentional Influx Management

Underbalanced drilling deliberately maintains bottomhole pressure below formation pressure to enhance reservoir productivity and minimize formation damage. In this scenario, the hydrostatic head is intentionally maintained at a level that is insufficient to prevent influx.

The well is expected to flow during drilling. Therefore, the primary barrier cannot be the hydrostatic head. Instead, the primary barrier becomes the surface pressure containment and processing system. This includes the rotating control head, choke manifold, separator, and flare system.

Control is achieved by managing flow at the surface rather than preventing influx at the bottomhole. The barrier philosophy shifts from exclusion of formation fluids to controlled handling of formation fluids.

4. Pressurized Mud Cap Drilling (PMCD): Surface Pressure as the Barrier

Pressurized Mud Cap Drilling is typically used in severe loss zones where returns to surface are not possible. In this method, drilling fluid is pumped into the well while returns are intentionally lost to the formation. Surface pressure is maintained to achieve the desired bottomhole pressure.

Because there is no conventional return column to establish a predictable hydrostatic gradient, hydrostatic head alone cannot be relied upon as a barrier. Bottomhole pressure depends on applied surface pressure. If that pressure is lost, well control is compromised.

Thus, the primary barrier is the pressurized surface system and associated equipment.

5. Coiled Tubing (CT) Live Well Intervention: Mechanical Barrier Philosophy

Coiled tubing operations introduce a fundamental shift in barrier philosophy. According to API RP 16ST, weighted fluid is not considered a barrier in CT well control systems. This distinction exists because CT operations are typically performed on live wells and involve continuous pipe movement.

Unlike conventional drilling, coiled tubing does not rely on killing the well before intervention. The tubing is inserted into a pressurized well through a stripper (packoff element), and the well remains under pressure throughout the operation.

Hydrostatic head is not credited as a barrier for several reasons. First, continuous pipe movement creates swab and surge effects that can temporarily reduce bottomhole pressure. Second, most coil tubing jobs are performed in smaller ID casings or completions, where the annular space is small, enabling rapid gas migration and pressure changes. Third, hydrostatic pressure cannot be pressure tested in the same manner as mechanical equipment.

For these reasons, CT operations rely on a tested mechanical barrier envelope. The primary barrier typically includes the stripper element and dual check valves in the bottomhole assembly. The secondary barrier comprises BOP rams and surface pressure-control equipment. These barriers are pressure tested at both low and high pressures prior to operation.

In CT, the industry emphasizes that well control must be achieved through tested mechanical integrity, not calculated hydrostatic assumptions.

6. Snubbing Operations: Running Pipe into a Live Well

Snubbing operations are carried out when a jointed pipe must be run into a well that is still under pressure. Unlike conventional workovers, in which the well is killed before the pipe is handled, snubbing is used when killing the well is either undesirable or impractical. The well remains “live” throughout the operation.

Because the well is under pressure, hydrostatic head alone cannot be relied upon to maintain control. In many snubbing jobs, the fluid in the well may not be heavy enough to fully overbalance the formation. Moreover, running pipe into the well changes the pressure profile. As the pipe is forced into the well against the well pressure, displacement effects occur. Similarly, when the pipe is pulled, swab effects can temporarily reduce bottomhole pressure. These dynamic conditions mean that the hydrostatic column may not remain a stable or sufficient barrier by itself.

For this reason, snubbing operations primarily rely on mechanical pressure-control equipment. The snubbing unit works in conjunction with:

Annular preventers that seal around the pipe

Pipe rams that close and hold pressure on a specific pipe size

Blind or shear rams for emergency sealing

Stripping systems that allow pipe movement while maintaining a seal

These components form the pressure containment envelope. They are designed, rated, and tested to withstand anticipated surface and well pressures. In practical terms, the steel and elastomer seals, not the mud weight, are what prevent uncontrolled flow.

Just like in coiled tubing operations, every barrier element in a snubbing spread must be pressure tested before use. Low- and high-pressure tests confirm that the seals hold and that the system can contain the expected loads. The barrier must also be independently verifiable. That means its integrity can be confirmed without relying on assumptions about fluid density or calculated bottomhole pressure. Mechanical integrity is demonstrated, not inferred.

7. Completion and Perforating Operations Under Underbalance

In some completion designs, the well is intentionally kept underbalanced during perforating. The purpose is to allow immediate inflow from the reservoir once the formation is perforated. This approach can improve cleanup, reduce formation damage, and enhance productivity.

In these situations, the hydrostatic head is deliberately kept insufficient to allow formation flow as a part of the completion strategy. Since the well is intentionally underbalanced, the fluid column cannot be considered a barrier.

Well control instead relies on mechanical isolation and surface pressure control systems. Typical barrier elements include:

A production packer that isolates the annulus and anchors the completion string

A lubricator assembly that allows perforating guns to be run in and retrieved under pressure

Surface pressure control equipment, such as valves and rams

The lubricator is pressure tested before perforating guns are introduced into the well. This ensures that when the guns are retrieved after firing, the well remains contained. The packer provides downhole isolation, and the surface equipment provides containment during tool movement.

Here again, the barrier philosophy shifts from preventing inflow at the bottomhole to safely containing and controlling inflow at the surface.

A Clear Decision Logic for Drilling and Completion Professionals

Hydrostatic head is a primary barrier only when certain basic conditions are met.

First, the mud weight alone must keep the bottomhole pressure above the formation pressure. If the well depends on surface-applied pressure or active choke management to remain overbalanced, the hydrostatic head is no longer acting independently.

Second, the well must remain overbalanced even if surface pressure is removed. If shutting down pumps or losing surface backpressure causes bottomhole pressure to fall below formation pressure, then the hydrostatic column by itself is not the controlling barrier.

Third, the hydrostatic column must be stable. It should not depend on dynamic factors such as continuous pipe movement, fluctuating surface pressure, losses, barite sag, gas influx, or managed pressure adjustments. A barrier that changes with operating conditions is not a fully independent static barrier.

If any of these conditions are not met, the primary barrier shifts. It may become a mechanical containment system, as in snubbing or coiled tubing. It may become a managed pressure system, as in MPD. Or it may be a combination of mechanical isolation and surface pressure control, as in underbalanced perforating.

The key question to ask in any operation is simple:

If surface systems fail or dynamic conditions change, does the well remain controlled solely by the hydrostatic column?

If the answer is no, then the hydrostatic head is not the primary barrier. Understanding this distinction allows drilling and completion professionals to properly identify, test, and monitor the true barrier system in place.

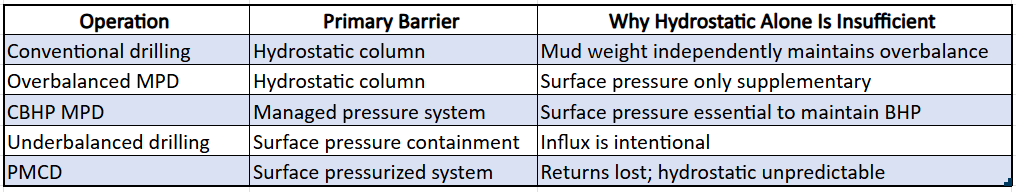

Comparative Summary Table

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Hydrostatic Head a Reliable Barrier?

Yes — when properly designed, maintained, and monitored in conventional overbalanced drilling.

It becomes less robust when:

Pressure margins are very small

The well is dynamically operated

Active systems are required to maintain pressure

Formation conditions are unstable

Why do standards prefer mechanical barriers in CT?

Because mechanical barriers can be pressure tested, verified, and monitored independently of dynamic well conditions, and most coil tubing operations are carried out in a live well situation (not a dead well)

Is dynamic pressure control inherently less safe?

Not necessarily. It requires higher procedural discipline, redundancy, and contingency planning.

Final Perspective

Hydrostatic head remains the foundation of well control philosophy. However, modern drilling and intervention techniques have introduced scenarios in which well control depends on active systems, mechanical containment, or controlled-influx handling.

For drilling professionals, the critical question is not simply, “What is the mud weight?” but rather:

“If surface pressure is lost or circulation stops, does the well remain controlled?”

If the answer is no, the hydrostatic head is not the sole primary barrier.

Understanding this distinction is essential for safe planning, risk assessment, and operational execution across drilling, MPD, coiled tubing, and completion activities.

References

API. 2018. API Recommended Practice 16ST: Coiled Tubing Well Control Equipment Systems, 2nd ed. Washington, DC: API Publishing Services.

API. 2021. API Standard 53: Blowout Prevention Equipment Systems for Drilling Wells, 5th ed. Washington, DC: API Publishing Services.

IOGP. 2016. Report 476: Well Integrity Guidelines. International Association of Oil & Gas Producers.

NORSOK. 2013. NORSOK D-010: Well Integrity in Drilling and Well Operations, Rev. 4. Standards Norway.

SPE. Various Authors. Technical papers on Managed Pressure Drilling and Underbalanced Drilling Practices. Society of Petroleum Engineers.